Most people who gaze out over the ocean focus on its surface, whether glassy, foamy, or stormy. There are people today – and in the past – who when looking seaward did so with acute consciousness of its third dimension, either of the sea floor or of the volumetric waters themselves. In my book, Fathoming the Ocean, I argued that the mid-nineteenth century was a period of cultural as well as scientific discovery of the depths, spurred in part by the fantastic promise of submarine telegraphy to link continents. Here I explore two French sources I’ve recently encountered that reveal the extent of imaginary engagement with the undersea in the nineteenth-century – but I’ll end with a comment, based on an article that students in my History of the Ocean class read, about a group of people far from France who have an equally marked, though extremely different, cultural engagement with the undersea realm.

Wind is full of this mystery. So, too, is the sea.

Like wind, it is composite in nature; under the waves of

water, which we can see, are waves of force, which we

cannot see. Its constituents are – everything. Of all the

jumbles of matter in the world the sea is the most indivisible and the most profound.

These lines from Victor Hugo’s novel, The Toilers of the Sea (1866) compare the undersea to the wind, positing both as forces but suggesting that the sea is all-encompassing in a way that air is not. The emphasis is on the “under the waves” part of the ocean, a “jumble of matter” judged more profound than the rest of the planet. This vision rests on a volumetric view of the ocean, which is not empty space but rather completely full. Like his compatriot Jules Verne, Hugo was a yachtsman who incorporated his seagoing experience as well as knowledge from new works of ocean science into his story, including from Matthew Fontaine Maury’s The Physical Geography of the Sea (1855) and Jules Michelet’s La Mer (1861). Also like Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, action in Hugo’s story draws the reader into the depths of the ocean, most dramatically in the protagonist’s epic battle with an octopus.

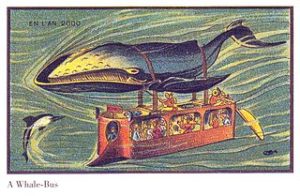

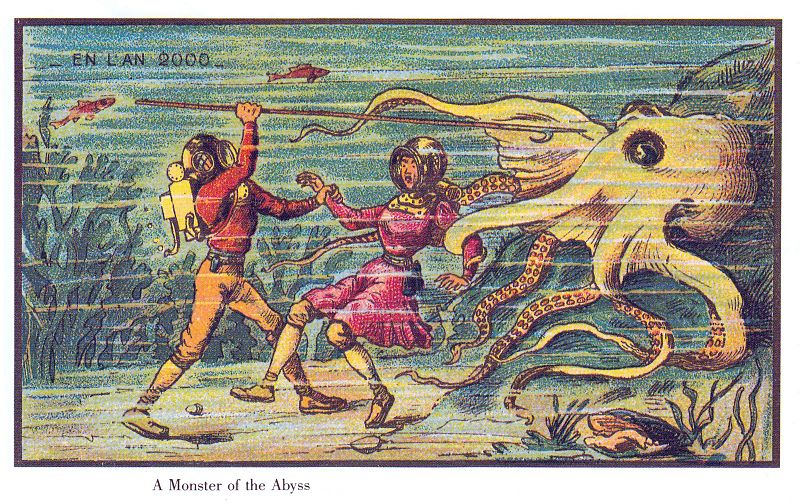

The octopus emerges again as “A Monster from the Abyss,” attacking a woman diver who is defended by a male diver wielding a spear in this image created by the French artist Jean-Marie Côté in 1899, one of a series of drawings imagining the future world of 2000. These paper cards were intended to be enclosed in cigarette or cigar boxes but they were never distributed. Much later the science fiction author Isaac Asimov discovered them and published them in his book Futuredays: A Nineteenth-Century Vision of the Year 2000 (1986). The fearsome octopus would have been a familiar trope to readers of Hugo and Verne, but other images from the series demonstrate a lively engagement with the undersea realm.

Divers ride on people-sized seahorses in one image, play croquet in another, and, in a third, race on the backs of large, sleek fish around a track, encouraged on by excited fans also clad in diving gear. In these and in the “Whale-bus” scene, tractable, domesticated ocean beasts are harnessed in service to human transportation and entertainment, a far cry from the threatening giant octopus.

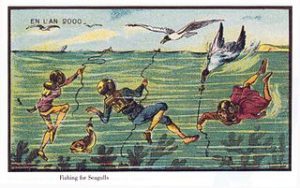

In a striking inversion, one image shows divers, two male and one female, “Fishing for Seagulls,” holding lines whose bait floats on the surface or can be pulled under the waves to entice gulls to dive for it. Nineteenth-century scientists often compared the atmosphere to the ocean’s depths to help their readers imagine the undersea, but this seagull fishing scenario reflects something more akin to the sentiment of the HMS Challenger naturalist Henry Mosely, who after four years at sea mused, “We live in the depths of the atmosphere as deep-sea animals live in the depths of the sea.” (Notes by a Naturalist, 1892, pp. 517-18).

Science and technology fueled the nineteenth-century undersea imaginary, but that era’s cultural discovery of the ocean’s third dimension was not the first. Around the globe and through time, groups of people living by and with the ocean have engaged with its totality, not just its surface or with things that could be plucked out from it. An anthropological study of the Polynesian island of Anuta in the Solomon Islands provides evidence of sophisticated and detailed mental mapping of the sea floor around the island by its residents, who depend on fishing for subsistence (Feinberg, et al, 2013). Close observation of the marine environment results in mental mapping of the seabed to assemble and pass along knowledge of good fishing locations, reefs close enough to the surface to endanger navigation, and distinct zones of depth and bottom type in concentric rings around the island. Places located and named on the mental map are as cultural as they are survival-related; some reefs are named for the first person to discover good fishing there, while a category exists for places that are revisited frequently by successors to the original explorer. The western anthropologist who worked with a small group of Anutans to render their mental map on paper focused at the outset on fringing reefs visible at the sea’s surface and ocean contours around the main passages, but Anutans, by contrast, “look to sea and observe an elaborate system of reefs that extends for miles in all directions.” The authors of article about Anutan sea floor mental mapping are mainly interested in contributing to understanding of indigenous cartography, but their work equally reveals animated engagement with the undersea realm such as must have been both common yet distinctive for many different groups of people in the past.

Richard Feinberg, Ute J. Dymon, Pu Paiaki, Pu Rangituteki, Pu Nukuriaki & Matthew Rollins (2003) ‘Drawing the Coral Heads’: Mental Mapping and its Physical Representation in a Polynesian Community, The Cartographic Journal, 40:3, 243-253, DOI: 10.1179/000870403225012943

Victor Hugo, The Toilers of the Sea (New York: The Modern Library, 2002), quote on p. 251.

Recent Posts

- Fathoming the Oceans Through History – TEDx TalkJuly 18, 2023

- An Appreciation of John GillisJanuary 20, 2021

- Ocean History and Confederate LegaciesJune 17, 2020

- Recreational Origins of Commercial Fishing TechnologyNovember 6, 2019

- Imagining the UnderseaJuly 30, 2019

- Welcome to Fathoming the OceanFebruary 23, 2019