As someone long interested in the histories of fisheries science and of nineteenth-century scientific study of the ocean, I eagerly picked up a recent scholarly article by fisheries scientist and maritime historian Trevor John Kenchington on the introduction of the otter trawl, a technology that has contributed significantly to industrial-scale exploitation of fish populations around the world.[1] While I expected a story about technology, innovation, and perhaps ultimately environmental devastation, it was a pleasure to find an unexpected – and yet a surprisingly familiar – ocean history story.

Trawls, especially otter trawls, have been singled out by fisheries historian W. Jeffrey Bolster for revolutionizing fishing by replacing passive gear with active pursuit of fish as well as by their indiscriminate capture of young with market-sized fish, along with everything else on the seabed.[2] Although some fisheries experts at the time of trawling’s introduction theorized that disturbing the sea floor would be beneficial, drawing an analogy to the plow in agriculture, we now know that bottom trawling causes long-lasting, negative effects to fisheries and to the marine environment.[3] Generally understood as a British innovation that emerged in the 1890s, otter trawling came into widespread use with new steam-powered vessels early in the twentieth century. The massive scale of otter trawling’s economic and environmental impact is clear in Kenchington’s analogy to industrial agriculture: “what the combine was to cultivated grains on land, the steam trawler was to wild animal protein from the sea.”[4] The origins of the technology have been similarly understood to lie firmly within the fisheries sector, reflecting the commercial importance of trawling world-wide.

Historians of technology will not be surprised to learn that development of otter trawling began earlier, proceeded more gradually, and included contributions from many more individuals and sectors than have been traditionally recognized. The surprise comes from learning that the otter trawl emerged in the context of recreation and science, rather than from commercial fisheries. The earliest references to otter trawls date from the 1860s and support the likelihood of several independent inventions of the use of weighted boards to spread the mouth of a net in order to gather animals from the seabed.

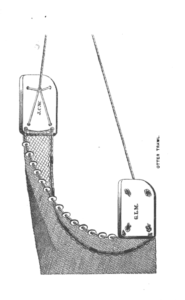

[Fig. 1 Otter Trawl from Wilcocks (1865), p. 155]

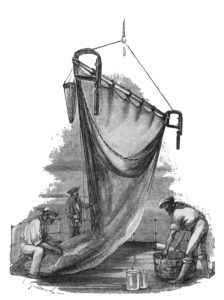

This technology diverged from beam trawling, in use in northern European coastal fisheries by the eighteenth century, in dispensing with the heavy, solid beam of wood held above the sea floor in an iron frame. An 1865 book to acquaint anglers and yachtsmen with ocean fishing briefly introduced the otter trawl as “highly spoken of by the crew,” although author J.C. Wilcocks admitted he had not yet personally seen one.[5] In subsequent editions, he provided more information including the assessment that the otter trawl was well-suited for amateurs because it was easier to handle and stow on yachts than the more cumbersome beam trawl.[6] This judgment echoes the advantages touted for the so-called “naturalist’s dredge” in the 1840s, which had been altered from dredges used by oyster fishers to make them easier for non-experts to deploy and also collapsible so they could be carried in carpetbags to sea-side holiday sites where the amateur naturalist-dredgers used them to collect marine fauna.[7]

[Fig. 2 Naturalist’s dredge]

Several companies began manufacturing otter trawls aimed at “amateur” customers in the 1870s.[8] The Plymouth firm, Hearder’s, which manufactured and sold fishing tackle and umbrellas, developed and marketed an otter trawl by 1875. A few years earlier, the company was chosen to provide beam trawls and other scientific collecting nets for the circumnavigation voyage of HMS Challenger in 1872-76, a commission likely enabled because Jonathan Hearder, its second-generation owner, was active in Plymouth scientific circles. Hearder’s advertised its otter trawls, in five sizes, after the experience of making gear for the Challenger. Interestingly, in the third month of the expedition, Captain George S. Nares experimented with replacing the dredge, which kept coming up full of ooze but with few specimens of scientific interest, with a 30-foot long fishing trawl that had a 13-foot beam. The attempt was successful enough to prompt further scientific use of the trawl, until it became a regular part of collecting on Challenger and thereafter.[9]

[Fig. 3 Challenger’s trawl]

[Fig. 3 Challenger’s trawl]

Indeed, Hearder’s subsequently provided otter trawls for the 1876-78 Norwegian North-Atlantic Expedition, one of a number of ocean science voyages undertaken by European nations in the wake of the Challenger expedition.[10]

Yachts had since the mid-nineteenth century provided platforms for naturalist-dredgers to collect from deeper waters than those reachable from the rowboats that the first scientific dredgers had employed, so it seems plausible that scientifically-minded sailors might similarly employ otter trawls.[11] Kenchington provides evidence from the 1883 International Fisheries Exhibition that otter trawls were adopted by yachtsmen for amateur fishing due to their ease of use. Although some commercial fishers also tried these early otter trawls, they were too light and too complex to use in heavy weather, among their other disadvantages for industrial purposes.[12] In short, otter trawls, which became historically firmly tied to the expansion of industrialized fisheries, were first developed for recreational and scientific use and only subsequently re-designed for commercial fisheries. That trajectory reflects patterns discernable in other instances of intersections between industry and science, such as the existence of toy steam engines before they were applied to industrial uses. For ocean history, the story of the otter trawl reminds us that categories of work and play on, and reaching into, the sea are – and have for a long time – been profoundly intertwined.

[1] Trevor John Kenchington, “The Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” Northern Mariner XXVIII (4)(Autumn 2018): 327-345.

[2] W. Jeffrey Bolster, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail (Harvard University Press, 2014), pp. 234-237.

[3] Ferdinand K.J. Oberle, Curt D.Storlazzi, and Till J.J.Hanebuth, “What a drag: Quantifying the global impact of chronic bottom trawling on continental shelf sediment,” Journal of Marine Systems 159(July 2016): 109-119.

[4] Kenchington, “Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” p. 345.

[5] J.C. Wilcocks, The Sea-fisherman (Gurnsey: Stephen Barbet, 1865), preface; quote on p. 156.

[6] Wilcocks, 2nd ed., cited in Kenchington, “Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” p. 332.

[7] Helen M. Rozwadowski, Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea (Harvard University Press, 2008), pp. 101-102.

[8] Kenchington, “Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” pp. 333-334.

[9] Rozwadowski, Fathoming the Ocean, pp. 169-170.

[10] Kenchington, “Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” p. 333.

[11] Rozwadowski, Fathoming the Ocean, pp. 117-130.

[12] Kenchington, “Introduction of the Otter Trawl,” p. 334.

Recent Posts

- Fathoming the Oceans Through History – TEDx TalkJuly 18, 2023

- An Appreciation of John GillisJanuary 20, 2021

- Ocean History and Confederate LegaciesJune 17, 2020

- Recreational Origins of Commercial Fishing TechnologyNovember 6, 2019

- Imagining the UnderseaJuly 30, 2019

- Welcome to Fathoming the OceanFebruary 23, 2019